The Star-Studded Chinese Restaurant Closed by McCarthyism

The owners, a couple whose marriage wasn't recognized for 11 years, had incredible lives.

Recently I was trying to tell someone that John Steinbeck may have ripped "The Grapes of Wrath" off from an un-famous woman writer, but I couldn't remember the details. This lead to me finding out, naturally, about L.A.'s most star-studded Chinese restaurant of the 1940s, owned by a Chinese-born cinematographer who invented many of the techniques we see on film today and who wasn't allowed to marry his wife, who he met in the '30s, until California's anti-miscegenation law was overturned in 1948.

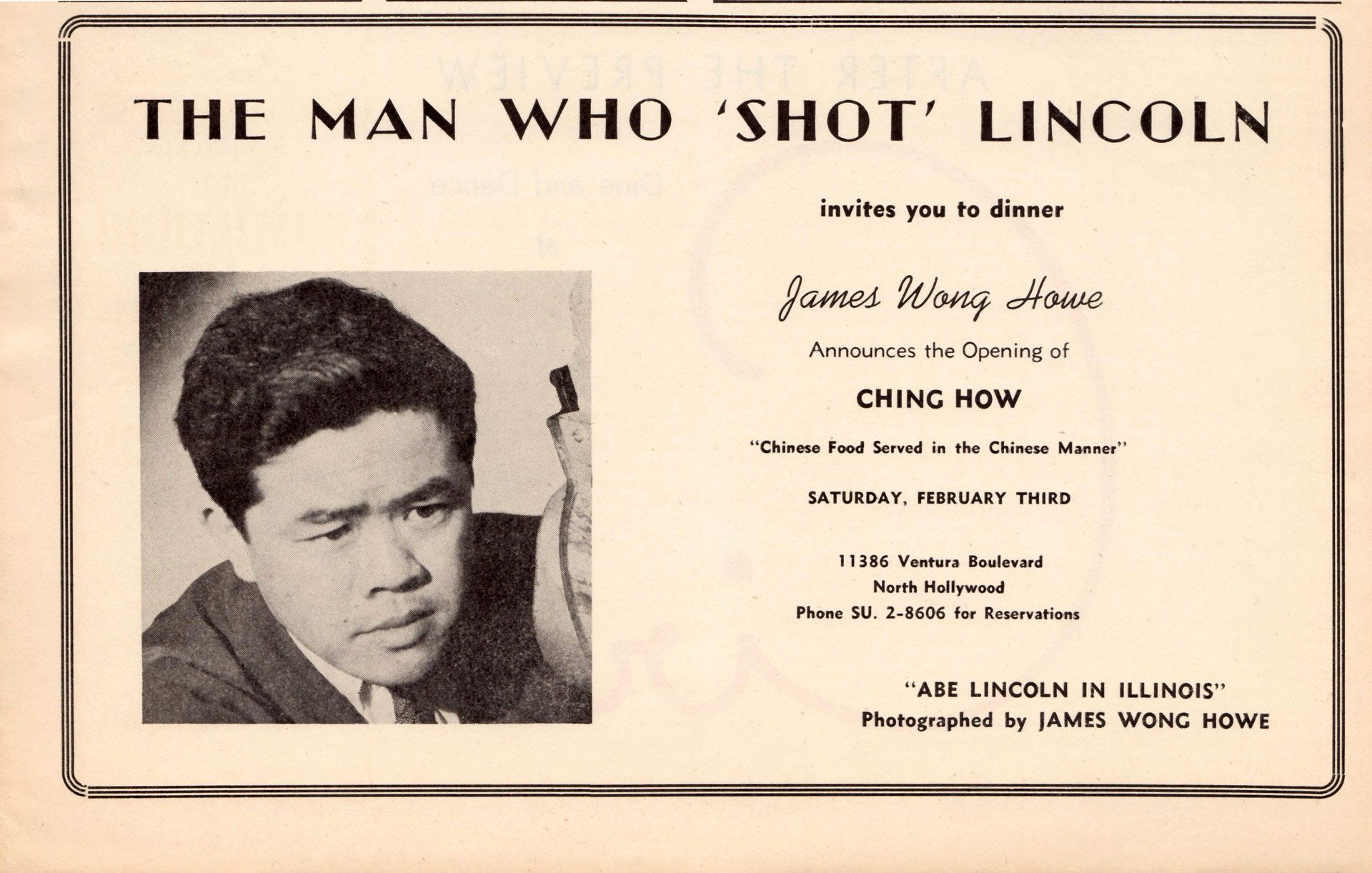

Cinematographer, #oscar winner and restaurateur James Wong Howe's ad for his Chinese restaurant from the September 1941 issue of Screen Actor magazine. Howe broke barriers as one of the most sought after cinematographers in Hollywood. #AAPI #asianamerican #representationmatters pic.twitter.com/6woWDWYAId

— SAG-AFTRA (@sagaftra) May 21, 2020

James Wong Howe was born in China, grew up in rural Washington state, attempted a boxing career in Oregon, and, starting in 1917, changed film history after making his way to Los Angeles.

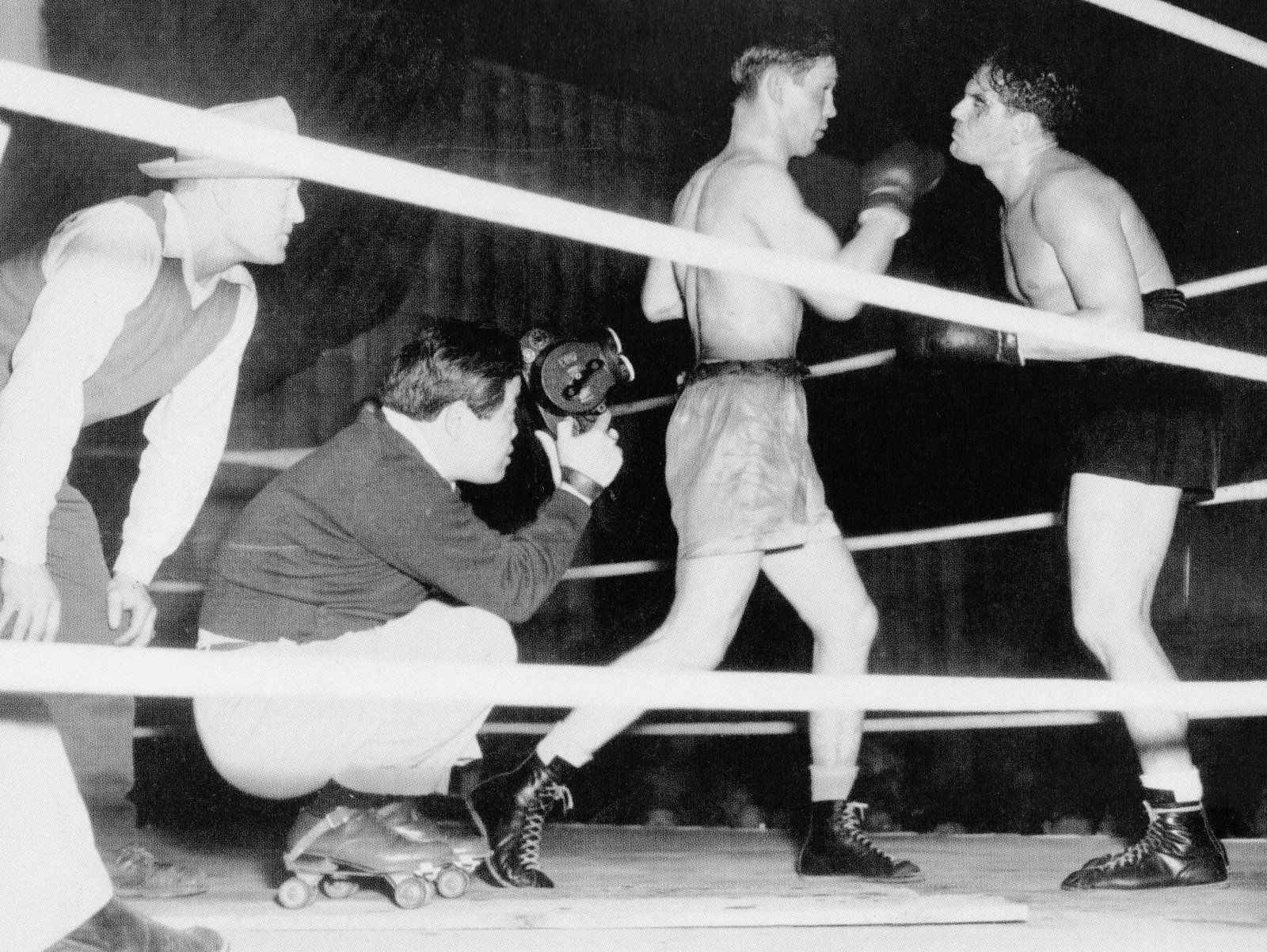

Criterion has a wonderful biography of Howe for the film buffs. He was an innovative cameraman and cinematographer from day one,; he was often asked for by actresses who felt that he captured their images in the most flattering way (most famously by adding black velvet-covered panels around lenses to make Mary Miles Minter's light blue eyes appear a richer color on screen). He was most known for his use of lights and shadows to tell a story, but he also invented camera dollies and put his whole body into his working, including shooting in a boxing ring while wearing roller skates, creating an atmosphere copied by Martin Scorsese in "Raging Bull." He also used deep focus 10 years before it was so famously utilized in "Citizen Kane."

Howe married Sanora Babb in France in 1937 —she's the woman mentioned above who wrote a novel just like "The Grapes of Wrath," but couldn't get it published. Babb moved to Los Angeles in 1929 and was occasionally homeless before compiling a regular roster of writing and editing clients at movie studios, radio stations, and magazines. She was an active communist and traveled to the Soviet Union in the '30s. In 1938 she started work at the Farm Security Administration. Her boss knew she was working on a book, and knew Steinbeck, and gave all of Babb's notes to Steinbeck. Who can say what happened after that. Steinbeck dedicated his book to said boss.

Howe and Babb were married in France because, as people of two different "races," they couldn't legally wed in California for another 11 years. I found multiple mentions of the fact that they maintain separate residences in the same building until their California marriage, and that this was due to Howe's "traditional Chinese values." There's no primary source that I can find attesting to that, and it seems a little condescending too, so I think it's more likely they lived separately (on paper, anyway) due to Howe's morals clause in his studio contracts. Those rules weren't just for actors.

When the couple opened Ching How in 1940, Chinese restaurants had existed in the U.S. for about 80 years, but had primarily been inexpensive, quick-service chop suey parlors. Ching How was one of the early upscale East Asian eateries in the country, serving more complex food and, as the ad above shows, boasting "tropical and Chinese drinks." (The fancification of Chinese restaurants coincided with the rise of tiki's popularity, and there was much overlap between the two genres.)

More: American Chinese Food

Though Chinese food was becoming more common in the U.S., there was a sense that non-Chinese customers needed some education to better enjoy the restaurant experience. Early ads for Ching How described the cuisine as "Chinese food served in the Chinese manner;" the menu contained this note: “Because many persons are unfamiliar with genuine Chinese food and sometimes find a menu confusing, we should like to suggest that you occasionally try leaving your dinner to the Chef.”

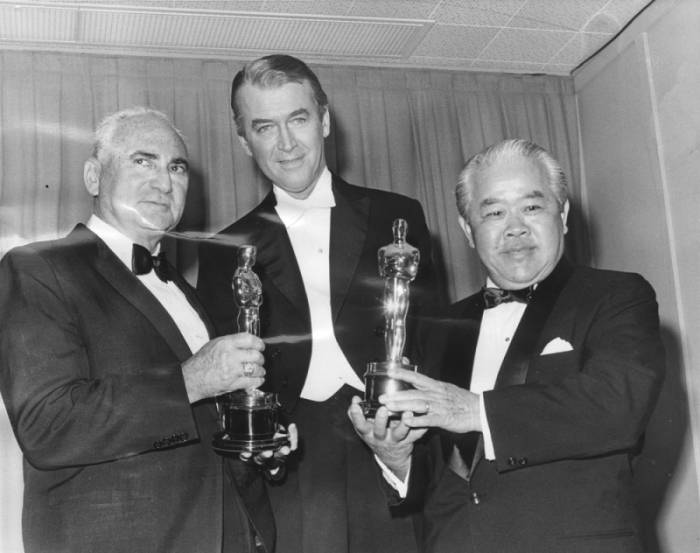

The restaurant was located in Studio City on Ventura Boulevard, already a great restaurant row. It was apparently popular especially with people, famous and not, who worked at the studios. It did close in 1952, though, after Babb was blacklisted by House Un-American Activities Committee. She moved to Mexico for two years, partly to save Howe's career, as he had been "graylisted," partly for being married to her and partly because he had visited China a few times to try to set up some co-productions with the film industry there. The plan worked: Howe won his first Academy Award in 1955; Babb came back and became a published novelist in 1958. (Her Dust Bowl novel, Whose Names Are Unknown, was finally published in 2004, a year before she died.)

Howe continued to innovate with his cinematography, freaking people out with his fisheye lenses in the horror movie Seconds in particular. He also worked as a professor at UCLA. He passed away in 1976, soon after receiving his tenth Academy Award nomination.

Howe is a known name only to a fairly small, film-obsessed audience, but everyone who watches movies has benefitted from his influence. And while Ching How was one standalone restaurant, Howe's belief that Chinese food was worthy of respect helped change an industry, and improves us all.